http://reference.medscape.com/

Ascites (shown) is the accumulation of fluid within the abdominal cavity. For patients with ascites, peritoneal paracentesis is performed to aspirate and analyze the ascitic fluid. It is one of the oldest medical procedures, dating back to approximately 20 BC. The collected fluid can be used to help determine the etiology of ascites, as well as to evaluate for infection or the presence of cancer. Causes of ascites include hepatic cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, heart failure, fulminant hepatic failure, portal vein thrombosis, peritoneal carcinomatosis, inflammation of the pancreas or biliary system, nephrotic syndrome, peritonitis, and ischemic or obstructed bowel.

Paracentesis is used for patients with ascites to determine etiology, differentiate transudates and exudates, detect the presence of cancerous cells, and/or diagnose suspected spontaneous or secondary bacterial peritonitis. Paracentesis may also be therapeutic in cases of respiratory compromise and abdominal pain or pressure secondary to ascites. Contraindications to paracentesis include an uncooperative patient, uncorrected bleeding diathesis, an acute abdomen that requires surgery, intra-abdominal adhesions, distended bowel, abdominal wall cellulitis at the site of puncture, and pregnancy. Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

A typical paracentesis/thoracentesis tray is shown. To perform a successful paracentesis, the following equipment is needed: 3 betadine swabs, 2 sterile drapes, sterile gloves, lidocaine 1% (5-mL ampule), a 10-mL syringe, two 22-gauge injection needles, a 25-gauge injection needle, no. 11 scalpel, 8-Fr catheter (over an 18-gauge × 7.5" needle with 3-way stopcock, self-sealing valve, and 5-mL Luer-Lok syringe), 60-mL syringe, 20-gauge introducer needle, tubing set with roller clamp, 3 specimen vials or collection bottles, drainage bag or vacuum container, four 4×4 sterile gauze pads, and a bandage

There are two recommended areas of abdominal wall entry for paracentesis: 2 cm below the umbilicus in the midline through the linea alba (blue arrow) or 5 cm superior and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine on either side (red arrows). Patients with severe ascites can be positioned supine. Patients with mild ascites may need to be positioned in the lateral decubitus position, with the skin entry site near the gurney.Position the patient in bed with the head elevated at 45-60 degrees to allow fluid to accumulate in the lower abdomen

Ultrasonography (shown) is recommended to verify the presence of a fluid pocket under the selected entry site in order to increase the rate of success. Ultrasound can also help the practitioner avoid small bowel adhesions or a distended urinary bladder below the selected entry point. To minimize complications, avoid areas of prominent veins, infected skin, or scar tissue. Ultrasound can also show the practitioner the distance from the skin to the fluid and provide information regarding the expected distance before fluid should be expected in the syringe

After the patient’s bladder has been emptied, position the patient and clean the area with Betadine or chlorhexidine solution in a circular fashion from the center out (shown), then apply a sterile drape. Explain the procedure to the patient and obtain a signed informed consent, if possible. Explain the risks, benefits, and alternatives

Use a 5-mL syringe and a 25-gauge needle to create a skin wheal of lidocaine at the entry site (shown).

Administer 4-5 mL of lidocaine with a longer 20-gauge needle along the expected path of catheter insertion (shown). Be sure to anesthetize down to the peritoneum. Alternate aspiration and injection during insertion until ascitic fluid is noted within the syringe and note the depth of the peritoneum. Obese patients will frequently have a significant amount of adipose tissue and a spinal needle may be necessary to reach the depth of the peritoneum.

Use the scalpel to make a small nick in the skin (shown) to allow the catheter to pass easily through the skin

Slowly insert the catheter perpendicular to the skin in small 5-mm increments (shown) to minimize the risk of vascular or bowel injury. Apply constant negative pressure when advancing the needle.

Loss of resistance will be felt as the needle enters the peritoneal cavity and ascitic fluid will fill the syringe (red arrow). Continue advancing the catheter an additional 2-5 mm (yellow arrow) to avoid misplacement of the catheter when advancing it into the peritoneal cavity.

At this point, firmly anchor the needle and syringe (blue arrows) to prevent further advancement of the needle into the peritoneum.

Next, use the opposing hand to hold the catheter and stopcock (green arrow), advancing the catheter over the needle (orange arrow) into the peritoneal cavity. Any resistance when advancing the catheter may indicate that the catheter has been misplaced into the subcutaneous tissue. If this occurs, withdraw the needle and catheter together as a unit in order to prevent the bevel from cutting the catheter.

While holding the stopcock, withdraw the needle. The self-sealing valve will prevent any fluid leak. The 3-way valve and stopcock control the flow of fluid and prevent fluid leak when no syringe or tubing is attached. Attach a 60-mL syringe to the stopcock and aspirate fluid (shown), then transfer the ascitic fluid to the specimen vials.

Connect one end of the collection tubing to the stopcock and the other end to the vacuum bottle (shown). Some practitioners recommend administering 25 mL of albumin (25% solution) for every 2 L of ascitic fluid removed. For example, a patient who had a 4-L paracentesis should receive 50 mL of intravenous albumin (25% solution) over 2 hours. The rationale for giving albumin is to avoid intravascular fluid shift and renal failure after a large-volume paracentesis.

The catheter may occasionally become occluded by the omentum or bowel. If this occurs, clamp the tubing, break the seal from the catheter, gently reposition or rotate the catheter, then reattach and unclamp the tubing. After the desired amount of fluid has been drained, remove the catheter and place a bandage over the puncture site. After paracentesis, some practitioners recommended that the patient remains supine in bed with vital signs checked hourly for 4 hours to monitor for hypotension

Noninfected ascitic fluid will be transparent and tinged yellow (shown). Possible complications from paracentesis include bowel perforation, hepatorenal syndrome, dilutional hyponatremia, introduction of infection, abdominal wall hematoma, major blood vessel laceration, persistent leak from the puncture site, hypotension after a large-volume paracentesis, and a catheter fragment left in the abdominal wall or cavity.

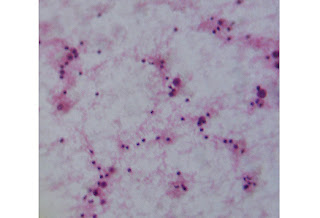

Patients with new-onset ascites of unknown etiology should have their peritoneal fluid sent for cytology (shown), cell count, albumin level, culture, total protein, and gram stain. The procedural note should include the following: indications for the procedure, relevant labs (INR, platelet count), procedural technique, sterile preparation, anesthetic used, amount of fluid obtained, character of fluid, estimated blood loss, fluid analysis results, any complications, and the patient’s condition immediately following the procedure. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Paracentesis is used for patients with ascites to determine etiology, differentiate transudates and exudates, detect the presence of cancerous cells, and/or diagnose suspected spontaneous or secondary bacterial peritonitis. Paracentesis may also be therapeutic in cases of respiratory compromise and abdominal pain or pressure secondary to ascites. Contraindications to paracentesis include an uncooperative patient, uncorrected bleeding diathesis, an acute abdomen that requires surgery, intra-abdominal adhesions, distended bowel, abdominal wall cellulitis at the site of puncture, and pregnancy. Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

A typical paracentesis/thoracentesis tray is shown. To perform a successful paracentesis, the following equipment is needed: 3 betadine swabs, 2 sterile drapes, sterile gloves, lidocaine 1% (5-mL ampule), a 10-mL syringe, two 22-gauge injection needles, a 25-gauge injection needle, no. 11 scalpel, 8-Fr catheter (over an 18-gauge × 7.5" needle with 3-way stopcock, self-sealing valve, and 5-mL Luer-Lok syringe), 60-mL syringe, 20-gauge introducer needle, tubing set with roller clamp, 3 specimen vials or collection bottles, drainage bag or vacuum container, four 4×4 sterile gauze pads, and a bandage

There are two recommended areas of abdominal wall entry for paracentesis: 2 cm below the umbilicus in the midline through the linea alba (blue arrow) or 5 cm superior and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine on either side (red arrows). Patients with severe ascites can be positioned supine. Patients with mild ascites may need to be positioned in the lateral decubitus position, with the skin entry site near the gurney.Position the patient in bed with the head elevated at 45-60 degrees to allow fluid to accumulate in the lower abdomen

Ultrasonography (shown) is recommended to verify the presence of a fluid pocket under the selected entry site in order to increase the rate of success. Ultrasound can also help the practitioner avoid small bowel adhesions or a distended urinary bladder below the selected entry point. To minimize complications, avoid areas of prominent veins, infected skin, or scar tissue. Ultrasound can also show the practitioner the distance from the skin to the fluid and provide information regarding the expected distance before fluid should be expected in the syringe

After the patient’s bladder has been emptied, position the patient and clean the area with Betadine or chlorhexidine solution in a circular fashion from the center out (shown), then apply a sterile drape. Explain the procedure to the patient and obtain a signed informed consent, if possible. Explain the risks, benefits, and alternatives

Use a 5-mL syringe and a 25-gauge needle to create a skin wheal of lidocaine at the entry site (shown).

Administer 4-5 mL of lidocaine with a longer 20-gauge needle along the expected path of catheter insertion (shown). Be sure to anesthetize down to the peritoneum. Alternate aspiration and injection during insertion until ascitic fluid is noted within the syringe and note the depth of the peritoneum. Obese patients will frequently have a significant amount of adipose tissue and a spinal needle may be necessary to reach the depth of the peritoneum.

Use the scalpel to make a small nick in the skin (shown) to allow the catheter to pass easily through the skin

Slowly insert the catheter perpendicular to the skin in small 5-mm increments (shown) to minimize the risk of vascular or bowel injury. Apply constant negative pressure when advancing the needle.

Loss of resistance will be felt as the needle enters the peritoneal cavity and ascitic fluid will fill the syringe (red arrow). Continue advancing the catheter an additional 2-5 mm (yellow arrow) to avoid misplacement of the catheter when advancing it into the peritoneal cavity.

At this point, firmly anchor the needle and syringe (blue arrows) to prevent further advancement of the needle into the peritoneum.

Next, use the opposing hand to hold the catheter and stopcock (green arrow), advancing the catheter over the needle (orange arrow) into the peritoneal cavity. Any resistance when advancing the catheter may indicate that the catheter has been misplaced into the subcutaneous tissue. If this occurs, withdraw the needle and catheter together as a unit in order to prevent the bevel from cutting the catheter.

While holding the stopcock, withdraw the needle. The self-sealing valve will prevent any fluid leak. The 3-way valve and stopcock control the flow of fluid and prevent fluid leak when no syringe or tubing is attached. Attach a 60-mL syringe to the stopcock and aspirate fluid (shown), then transfer the ascitic fluid to the specimen vials.

Connect one end of the collection tubing to the stopcock and the other end to the vacuum bottle (shown). Some practitioners recommend administering 25 mL of albumin (25% solution) for every 2 L of ascitic fluid removed. For example, a patient who had a 4-L paracentesis should receive 50 mL of intravenous albumin (25% solution) over 2 hours. The rationale for giving albumin is to avoid intravascular fluid shift and renal failure after a large-volume paracentesis.

The catheter may occasionally become occluded by the omentum or bowel. If this occurs, clamp the tubing, break the seal from the catheter, gently reposition or rotate the catheter, then reattach and unclamp the tubing. After the desired amount of fluid has been drained, remove the catheter and place a bandage over the puncture site. After paracentesis, some practitioners recommended that the patient remains supine in bed with vital signs checked hourly for 4 hours to monitor for hypotension

Noninfected ascitic fluid will be transparent and tinged yellow (shown). Possible complications from paracentesis include bowel perforation, hepatorenal syndrome, dilutional hyponatremia, introduction of infection, abdominal wall hematoma, major blood vessel laceration, persistent leak from the puncture site, hypotension after a large-volume paracentesis, and a catheter fragment left in the abdominal wall or cavity.

Patients with new-onset ascites of unknown etiology should have their peritoneal fluid sent for cytology (shown), cell count, albumin level, culture, total protein, and gram stain. The procedural note should include the following: indications for the procedure, relevant labs (INR, platelet count), procedural technique, sterile preparation, anesthetic used, amount of fluid obtained, character of fluid, estimated blood loss, fluid analysis results, any complications, and the patient’s condition immediately following the procedure. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

0 komentar :

Posting Komentar